Developing Leaders Who Coach

by Dr. Mike Armour

(Part 2 of 3)

Interviewer

You've described a coach as a facilitator. But when I think of coaches, what comes to mind is someone who is in charge and is calling the shots. That doesn't sound like a facilitator to me.

Armour

You've made a good observation. The most common image of a coach is someone who stalks the sidelines, barking out commands and signaling the next play. In sports like football, soccer, basketball, and hockey, this is the prevalent style of coaching.

But in other sports, such as golf or tennis, the coach is nowhere to be seen during the game itself. In fact, some sports prohibit the coach from being anywhere near the competition. Tactical decisions during the game must come from the athlete alone. And when something goes wrong, the athlete must take corrective action without input from the coach.

Executive coaching functions in basically the same way. Executive coaches facilitate rather than direct, because their goal is a client fully capable of self-direction once the game is underway and the coach is no longer around.

To enhance this self-reliance, coaches facilitate a specific type of dialogue. The dialogue is structured to force frequent reflection and introspection on the part of the person being coached. This introspection serves to strengthen inner resources and make these resources accessible at will.

It also engenders deeper self-understanding and clearer set of perspectives. Most of all, it enlarges the ability to autonomously generate appropriate insights, options, goals, strategies, and outlooks essential to sustained success.

Interviewer

Given these distinctions, is it best for leaders to focus on mentoring? Or on coaching?

Armour

Neither mentoring nor coaching is necessarily the "best" focus. Each one has its own unique contribution to make to the development of others. But the skill set in mentoring is easier to master.

Because mentoring deals with topics which are more general in nature and because it entails more narration and counsel than artful questioning on the part of mentor, the ability to mentor can be learned rather quickly.

After all, at one time or another most of us have had someone who mentored us about our life or career. They probably had no specialized training to be a mentor. They merely had a heart to help others by sharing what they had learned.

Leaders can therefore start to mentor with relative ease. Moreover, the skills which they hone as mentors are directly transferrable to coaching. Coaching merely layers other skills on top of the mentoring skill set. These added skills make coaching more challenging to learn.

But the advantage of coaching is that it has far more leverage to effect quick and lasting change than is true of training, consulting, or even mentoring.

Fortunately, you don't have to wait until you are an accomplished coach before you begin helping people enhance their skills or realize their goals. You can facilitate skill development by combining mentoring with one-on-one training, in a paired relationship which looks very much like coaching.

In fact, this very combination is the primary way that we've learned much of what we know. So my counsel to leaders is to become mentors first. Then, as you mentor, add occasional techniques of coaching until you are as comfortable with coaching as you are with mentoring.

Interviewer

If it takes time for leaders to develop coaching skills, how do companies provide for coaching in the meanwhile?

Armour

Companies meet this challenge in a variety of ways. Because mentoring is an easier skill to master, some companies make little effort to train managers and executives as coaches. Instead, the company sets its priority on training leaders to be good mentors. For coaching, the company then relies on external specialists.

A variant on this approach is to add professionally trained coaches to the HR staff. In this arrangement the company's leaders serve as mentors and these HR personnel provide in-house coaching. A variation on this strategy is to use in-house coaches for some assignments, external coaches for others.

Interviewer

Okay, but the more you talk about this, the more I wonder if busy executives and managers really have time to coach and mentor.

Armour

Well, let me ask this. Do they have time for conversations with people in their organization? After all, as leaders they're responsible for developing their people, aren't they? And don't they pursue this development in large part through conversation? Now, what if they were skilled at turning these developmental conversations into brief coaching or mentoring encounters?

You see, coaching and mentoring are not so much about how much time you spend with people, but about the way you structure conversations with them. Coaching conversations — and mentoring conversations, too, for that matter — don't need to be time-consuming. I've had coaching conversations which ran for hours and others which lasted only a few minutes.

Of course, formal coaching or mentoring relationships — those that fall under a structured company program — call for more extensive commitments of time. But these programs normally match executives to only one coaching or mentoring partner at a time. And without exception, executives who serve in this capacity find it rewarding, fulfilling, and well worth the sacrifice which they make to participate.

Interviewer

In other words, coaching and mentoring are both time well- spent for leaders.

Armour

Without question. Above everything else, leadership is a "people process." It's about rallying people around a common purpose, then motivating them and mobilizing them to achieve it. And the key phrase here is "achieve it." Leadership is ultimately about results. Only by achieving desired results does leadership fulfill its calling.

This makes for a natural marriage between leadership and coaching, since coaching also has this same passion for results. It seeks to improve effectiveness, accelerate achievement, and attain vital outcomes, all primary concerns for leadership.

Leaders who coach and mentor are fulfilling the third of three imperatives incumbent on leadership. The first is to know who your people are. The second is to know where you are taking them. And the third is to equip them for the journey. Coaching and mentoring equip people for the journey. Unlike counseling and therapy, which are called "people-helping" professions, coaching and mentoring are best described as "people-equipping."

Interviewer

So coaching is not an adjunct to leadership. It aligns directly with leadership's essential functions.

Armour

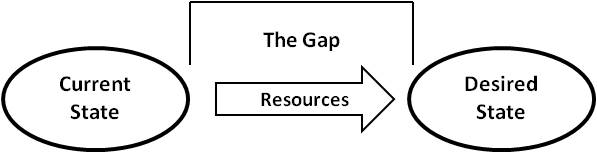

Precisely. Leadership and coaching are both future oriented. They set their vision on some desired future state.

- They begin by identifying this desired state.

- Next they analyze the gap between the current state and the desired one.

- Then they work to fill this gap with the resources required to reach the desired state.

Building resources is both the equipping function of leadership and the primary domain of coaching. The following illustration demonstrates the relationship between the current state, the desired state, and the resources to fill the gap in leadership and coaching alike:

Thus, in terms of their underlying structure, coaching and leadership are highly compatible. Because of this, good leaders immediately recognize the value of the current state/desired state model of coaching.

Interviewer

But can't mentoring, as you've defined it, function in this same current state/desired state structure?

Armour

In one sense it can. In fact, most mentoring which I've seen in the business world is less of the Merlin-Arthur type of activity, where someone is being readied for life, and more of an equipping effort to further a desired outcome for the company.

Yet, even when mentoring is conducted within the current state/ desired state model, it still differs from coaching in one vital regard. This difference revolves around the "locus of expertise." In mentoring, the primary expertise is resident in the mentor.

The same principle is found in training, consulting, and advising. In all of these disciplines the locus of expertise is in the service provider.

Coaching, by contrast, posits the locus of expertise in the one being coached. This parallels the relationship between coach and athlete in professional sports. Once an athlete is a professional, it's rare for the coach to have more athletic ability than the athlete. As a result, the role of the coach is less about imparting expertise and more about enhancing the inherent expertise of the athlete.

Executive and leadership coaching follows a similar pattern. The coach simply facilitates a conversation that surfaces latent ability within the person being coached and sharpens the abilities already evident. The ancient Greeks would have called this "education," which literally means to draw out what lies hidden inside.

When it comes to coaching, I think that we intuitively sense this unique locus of expertise, even if we have never articulated it. This accounts for our collective resistance to the term "coachee" as a name for the person being coached. Although you hear the word used occasionally, it has never caught on. Why not?

Perhaps it's because of what English words ending in "ee" typically denote. They usually identify the party in a relationship who is less knowledgeable or less in control. So we have words like "employee," "appointee," "inductee," "trainee," and even "mentee." But somehow "coachee" just doesn't sound right to the ear of most native English speakers. And I attribute this dissonance to our unconscious recognition that in coaching (in contrast to other people-equipping endeavors), the locus of expertise is found within the person being coached, not in the one doing the coaching.

Interviewer

When a leader coaches, however — especially in a business context — doesn't the leader usually have more subject matter expertise than the one being coached?

Armour

In general that's true. But in terms of how the leader structures the coaching conversation, the leader assumes the place and function of a facilitator, not the subject matter expert. Acting as a facilitator, the leader draws out the expertise and abilities of the other person, whereas the job of a trainer or consultant is to impart expertise and skill.

This is why effective executive coaches can provide their services across a broad spectrum of industries, even though they may know little about the inner workings of these individual industries. It's rare, indeed, for an external coach to have the industry expertise of the one being coached. But unlike consultants and trainers, coaches are not required to bring subject-matter expertise to the coaching relationship. Instead, the coach is facilitating the other party's learning process.

The word "facilitate" comes from a Latin word meaning "easy." The function of a facilitator is to make something easier to accomplish. As a facilitator, the coach helps people tap into every resource at their disposal and to do so more effortlessly, thus making it easier (and therefore quicker) for them to achieve desired outcomes.

Interviewer

Then coaches never share their own expertise with the person being coached?

Armour

Quite the contrary. The time constraints of a coaching conversation or the urgency of matters at hand can require the coach to set aside the coaching function and briefly put on another hat.

In such instances the coach momentarily becomes a trainer, an advisor, or a consultant in order to convey something essential — a piece of vital information, an element of knowledge, or even a new skill. But as quickly as this essential information is conveyed, the coach immediately shifts back into the coaching role.

Let me give you a common example from my coaching experience. In the course of a coaching conversation, the person whom I'm coaching hits a roadblock. He or she will say something like, "I just don't know how to analyze this situation." My thought goes immediately to a helpful analytical model found in a certain book. So I ask, "Have you read such-and-such a book?"

If the client has read the book and grasps the model, I ask, "In what ways could this model be helpful in your analysis?"Notice that I don't make any application myself. That's the client's job. My function is to keep asking questions to help the client uncover new insights from the model.

But what if this person says, "No, I don't know that book"? At this point I'm likely to take off my coaching hat and put on my training hat. I quickly provide a short overview of the book and its primary theme. Then I sketch out the model on a sheet of paper and explain it. With this training task complete, I take off the training hat, don the coaching hat once more, and ask the coaching question: "In what ways could this model be helpful in your analysis??

The key for you as a coach is to be purposeful when you change hats and to be aware of the change when you make it. With my students I sometimes describe a coaching conversation as a dance in which you move repeatedly away from the coaching position, then back to it again. At times the move takes us to consulting, at other times to mentoring. The next time the move may be to training or advising. But the goal is always to return to the coaching function as swiftly as possible, because that's where the client's learning is most effectively facilitated.

Interviewer

Is there a simple way to know when you've begun to function in one of these other arenas?

Armour

Perhaps the simplest way is to ask yourself, "Given the way that this conversation is presently structured, would an observer believe that the locus of expertise is within me or inside the other party?" If the answer is "within me," then you've stepped out of the coaching position, at least for the moment.

A second way to determine whether you are coaching or not is to compare the amount of time that you and the other party are talking. If you are talking more than 20% of the time, there's a high likelihood that you have set aside coaching to play the role of consultant, trainer, mentor, or advisor.

Remember, coaching conversations are intended to help the other party self-discover. And people self-discover only through reflection and talking things out. If you are dominating the conversation, you are not providing an opportunity for reflection to occur. And you certainly are not allowing time for the reflection to clarify itself through verbal expression.